December 19, 2016 from The Best American Poetry blog

A Husbandry of Risk and Want in a House Run by Mothers: Dante Di Stefano Reviews Tommye Blount’s What Are We Not For

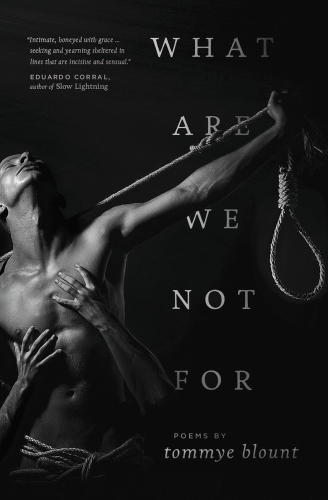

What Are We Not For

Tommye Blount

Bull City Press, 2016

Tommye Blount’s debut chapbook, What Are We Not For, artfully explores what it means to live inside a black queer body at this particular time in American history. Blount’s sinewy poems are bound together with countless silken ties of desire, fear, and affection for the world in all of its wounding might. Ranging from tightly made free verse, to sonnet, to villanelle, these poems perpetually shrapnel into each other. Each poem shuts its mouth “around the rough ramble of wordlessness” and redirects its gaze to the pulsing lycanthropic chiefdom a body carries within its provinces. In this collection, the mutt of the first poem, “Bareback Aubade with the Dog,” who snaps the thin leash of yes, transforms into the werewolf of a later poem, who is beaten “until skin becomes wound/ then scab then hide.” What Susan Howe said of Emily Dickinson could be said of Tommye Blount as well: “Poetry leads past possession of self to transfiguration beyond gender.” However, Blount never forgets the whiplash logic of a culture founded on the destruction of black bodies. As the speaker in “The Tongue” notes: “…I have the tongue/ of some endangered animal. No one can understand me.” What Are We Not For retrieves the seams in the seamless transition from scar tissue to carapace. More importantly, this powerful collection celebrates the “sweet body” and the affirmation that buzzes inside the hive of the self at its most sated and at its most insatiable.

For Blount, nevertheless, the sweet body is also the site of unspeakable pain. A dog, forever barking, forever muzzled, runs through these poems toward that pain. The figure of Pinocchio, which recurs throughout the poems, foregrounds that pain in his interrogations of realness. “Geppetto’s Lament” begins: “Off to mess with what I made him, the boy/ forgets he is not a boy. Forgets these/ strings and this paddle, shaped like a cross, are/ in my hands.” The pain of Pinocchio, who in the poem, “Pine,” cuts the inside of his thighs with his father’s whittling knife, emblematizes the struggle of anyone who attempts to define the self against normative cultural expectations. Blount deftly questions the surreptitious pacts and the hidden strings that bind son to father, beloved to lover, lynching victim to crowd, body to spirit, spirit to word. As the title poem notes:

What Are We Not For

but to be broken

like the deer resting on the side of the highway,

in a bed made of

its insides? Isn’t the scene

always the same—the rump and legs

frozen in one last kick?

I, too, have lost my gaze,

the grip of the wheel—

like the one that plowed into

the deer. Wheel, will—it’s all the same.

And the ear does fail me at times,

as it must have the deer

that should have listened better.

Francine, on the other end of the line,

tells me I’m not listening; to listen

to my body or I won’t last long. We never

last long, do we? It all breaks—

the line pulsing forward, the line pause,

the long bone of it all. After all,

I am a broken animal. I am brokered

in the name of the wheel.

Despite this constant breaking, Tommye Blount stays on the line. He knows that our bodies may be museums, but they contain more than mere artifact. The lynching of Frank Embree in 1899 appears in one window of the body, right next to Matthew Shepard’s murderer, Aaron McKinney, in 1998. And yet, if the body is a site of trauma, it is also a dance floor. Channeling the famous choreographer, Willi Ninja, Blount defiantly exclaims, “Bitch, give me a body/ and I will show you how it works” and jubilantly continues: “One day I will show you the world/ is one big ass ball—/ / a house run by mothers.” Reading this chapbook, one husbands risk and want and pain and sorrow, only to access ultimately such unfettered joy. Reading What Are We Not For is as necessary as breathing, grieving, and loving.

Dante Di Stefano is the author of Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight (Brighthorse Books, 2016). He is the winner of the 2015 Red Hen Press Poetry Award, the Crab Orchard Review‘s 2016 Special Issue Feature Award in Poetry, and the 2016 Manchester Poetry Prize,